When teams begin using OKRs, one of the first sticking points appears before the quarter even starts: everyone understands the objectives, but the Key Results feel uncertain.

Teams can describe what they plan to work on, what they hope to improve, and what they intend to deliver - but they can’t always articulate the outcome they expect those efforts to produce.

It’s not because teams don’t care about results. It’s because the idea of “outcomes” sounds simple in theory but becomes complicated in practice. Startups move quickly, priorities shift often, baselines aren’t always documented, and ownership can be fluid.

In that environment, writing clear, measurable outcomes becomes harder than expected.

But outcomes are the part of OKRs that give the framework its structure. Without them, OKRs become a list of ambitions and projects instead of a way to evaluate progress.

This article explains what outcomes actually are, why teams struggle to define them, and how getting them right changes the way OKRs work across the quarter.

The Real Issue With OKR Outcomes

In early-stage companies, the work itself is obvious: build features, publish content, experiment with channels, talk to customers, close deals, improve processes.

These activities fill calendars and create momentum, but they don’t tell you whether the business is moving in the right direction.

Outcomes matter because they describe what should change if the work succeeds.

The challenge is that outcomes require teams to commit to a specific shift. When a company is still finding its footing, that level of clarity can feel risky. It’s easier to say “we’re launching a new onboarding flow” than to say “onboarding completion increases to 70%.” One describes action; the other creates accountability.

So teams write OKRs that sound polished but don’t measure impact. They describe intentions rather than changes. They outline deliverables rather than results.

And as the OKR cycle continues, the team lacks a reliable way to determine whether the work is doing what it was meant to do.

The problem isn’t a lack of understanding. It’s that defining outcomes forces clarity that many early-stage teams haven’t yet built into their planning habits.

What Teams Actually Mean When They Say “Outcome”

An outcome isn’t a description of work completed, and it isn’t a guess about which projects will succeed. It’s the specific improvement the team expects by the end of the cycle.

Most outcome-based KRs fit into a few categories:

- Performance shifts: conversion, activation, efficiency

- User behavior changes: adoption, engagement, completion

- Operational improvements: cycle time, response time, throughput

- Quality reductions: defects, churn drivers, support load

The important point is that an outcome measures a change in the business, not a list of tasks.

For example:

- Activity: Rebuild onboarding

- Outcome: Increase onboarding completion from 42% → 70%

Only the second tells you whether the work made a difference.

Without outcomes, teams can stay busy, ship work, and still lack an objective sense of whether anything improved.

Why Most Teams Get Outcomes Wrong

Teams usually struggle with outcomes for predictable reasons.

The first is uncertain baselines. Teams know what they want to improve but don’t always know the current number. Without a baseline, setting a target feels speculative, so they avoid committing.

The second is shared ownership. When a result spans multiple roles or functions, no single person feels responsible for moving the metric. To avoid awkward accountability, teams default to tasks.

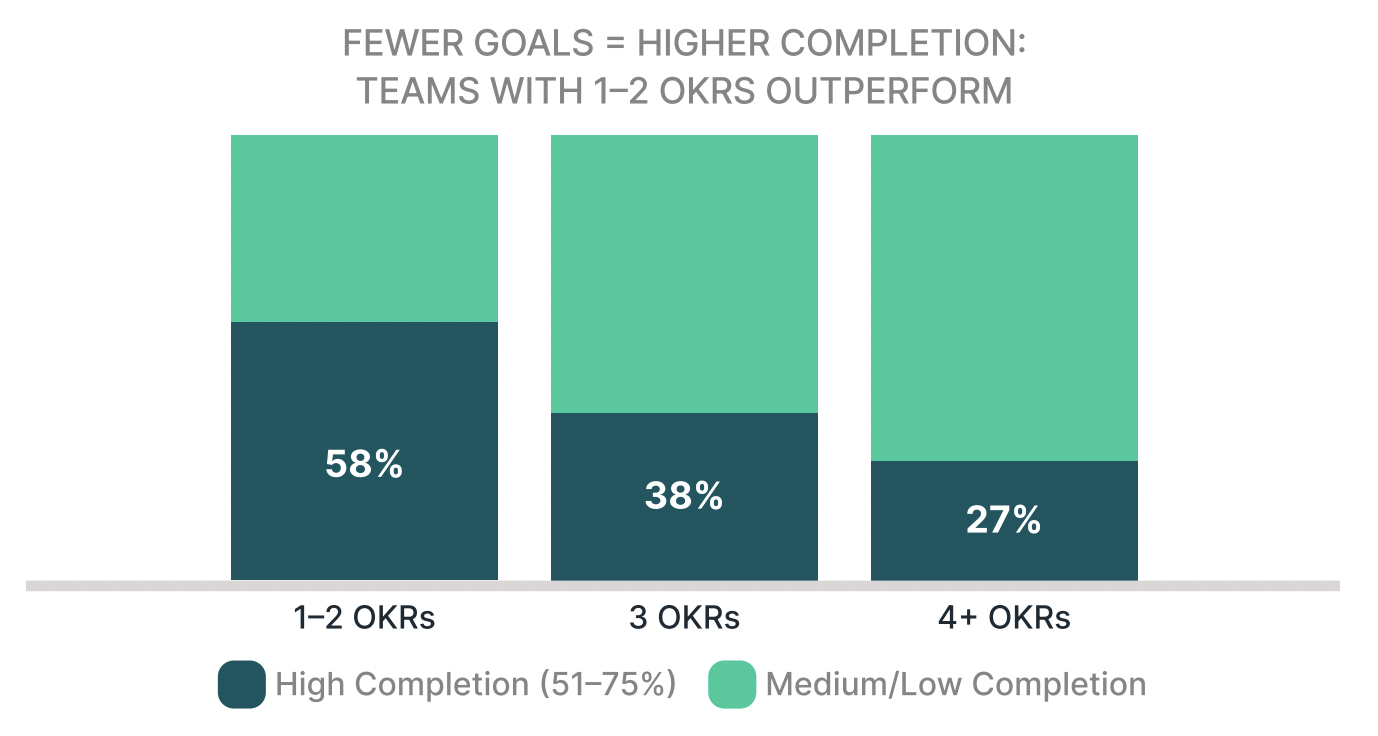

The third is scope overload. When teams set too many OKRs, each one receives less attention. Defining outcomes requires focus - a small number of objectives and a concise set of KRs. When the surface area is too large, teams write broad, vague KRs because they feel safer.

Finally, there’s a bias toward tangible work. Activities feel concrete and controllable. Outcomes depend on user behavior, sequencing, assumptions, and market conditions. Teams gravitate toward the work they can directly deliver, even when the value comes from what that work produces.

These challenges aren’t unusual. They’re part of the early OKR learning curve.

What Strong Outcomes Look Like in Practice

Teams that define outcomes well describe the change they expect without overengineering the KR. Their Key Results are specific, measurable, and clearly tied to the objective.

A product team improving activation might commit to:

- Increase onboarding completion from 42% → 70%

- Raise Day-7 activation from 22% → 35%

- Increase engagement with core feature X from 18% → 40%

A growth team might aim for:

- Improve visitor-to-trial conversion from 3.1% → 5%

- Reduce CAC payback from 9.2 → 6.5 months

- Increase organic signups from 160 → 300 per month

An operations team might focus on:

- Reduce support response time from 18 hours → 6 hours

- Decrease cycle time from 14 days → 9 days

- Lower defect rate from 27% → 12%

Good outcomes share several traits: the baseline is known, the target is clear, one person owns the metric, and multiple approaches could achieve the improvement. Outcomes should create space to adapt, not dictate the project list.

How Outcomes Change the Experience of Running OKRs

When outcomes are written well, weekly check-ins become more meaningful because progress is tied to movement in the metric, not a list of completed tasks.

Updates shift from “we shipped X” to “the metric moved four points” or “the result hasn’t changed; we may need to adjust.”

Outcomes also improve prioritization. If a project doesn’t contribute to the improvement described in a Key Result, it becomes easier to pause or remove it.

Risk becomes visible earlier. By reviewing movement weekly, teams see stalls long before the end of the quarter and can redirect sooner.

Over time, teams develop a clearer sense of which efforts reliably move which metrics. This improves planning and makes future cycles more predictable.

Getting Better at Outcomes Over Time

Teams rarely write perfect outcome-based KRs in their first cycle.

It usually takes a couple of quarters before baselines are clearer, targets feel grounded, and ownership becomes more natural. The important part is consistency - reviewing what worked, what didn’t, and what to adjust next cycle.

As outcome definition improves, OKRs shift from a quarterly planning exercise to a reliable operating rhythm. That’s where the real value appears: clearer priorities, faster decisions, and a more predictable path to progress.